We need to go back to basics: get out of the process!

Since the early release of the agile manifesto, much have been said about what agile is really about. People have fought epic battles over whether distributed team works or not, whether it is Scrum or Kanban, Lean, DSDM or Crystal Clear the “right” choice, whether the standup daily meeting has to be held when the sunshines or when the sunsets, and so on. Much energy has been spent on such kind of discussion, and this really doesn’t seems to add up in the end.

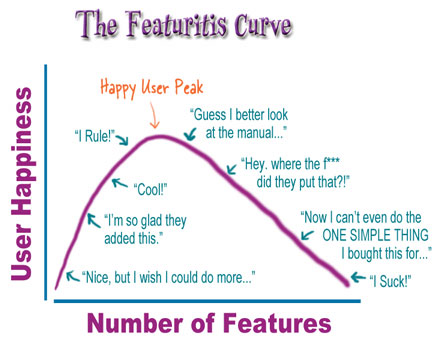

Despite what’s written on the agile manifesto (don’t forget the twelve principles as well), a lot of people are still stuck with the basics. Still talking about processes, estimation, certificates, and what the role of the Scrum Master is versus the role of the Product Owner. While these questions are indeed important and matter in our day, we can not be carried away by them, and focus solely on them.

People over processes

People over processes is the first value stated in the agile manifesto, but yet the most misinterpreted and forgotten one. Please don’t get me wrong: processes are really important. But people are more. It’s there, in the manifesto. Misinterpreted because it’s not about destroying processes – this is a surprisingly common misconclusion. And forgotten because even within the agile community, people focus way too much on processes.

While there are tons of books on processes, be they agile or not, and on software engineering, they are basically books on tools and techniques. Where are the books on the human relations involved in software craftsmanship? There are a few authors that have been on this subject, two of them I had the opportunity to meet in person: Lyssa Adkins and Jurgen Appelo. I’ll not get into details about their books, because this is not the point of this article. They’re both great books, and over the past couple of years they’ve changed my view of the world of software development.

Stop blaming the process, start caring about your culture

I’ve participated in two company-wide agile adoptions, and on both cases the main obstacle, the major issue we had to deal in a day-to-day basis was the culture in place. The real struggle was about changing the internal culture, not the processes. If you can read and follow instructions, you can grab a Scrum guide and have it running in almost no time. It’s dead simple. The thing is the aftermath, which isn’t written anywhere: making agile stuck, changing the culture. This is really hard. Culture is defined as “The set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution, organization, or group” (source: Wikipedia).

So far, I’ve come to one conclusion: there’s no right or wrong way to “do” agile. There are cultures in which the introduction of a new process is easier, there are cultures that makes it almost impossible to change. And it’s really easy to just blame the process and get away with it: the process just can’t fight back.

But how do we fix a broken culture?

This is an answer that you’ll have to figure out for yourself, mainly because there isn’t a right one. And cultures are also not broken, they’re just different. And we have come to live and understand in a world full with differences, so it’s not impossible. It might be hard.

What agile is really about

Agile development is really about values and principles, not processes. For some companies, agile is just a different way of doing things. It’s easy, and it just works. In other companies, adopting agile means a disruptive, ground-breaking and throughout transformation in the company culture. Process is secondary. So, again, human relations got in the way. So, if you’re struggling with your agile implementation, don’t give up. Read the manifesto, see the values and principles there.

Don’t look for what’s wrong with your culture in place, look for what’s different. And then start asking why it’s different. Generally, when you ask ‘why’ on something, on the third depth (from the 5 Why’s problem-solving technique) you’ll see what’s really there, the real root cause of that social convention or behavior. And then you’ll be surely able to bridge it in a different way to the agile manifesto. I’m yet to see a businessman, an entrepreneur, a manager, no matter what level they’re on the corporate ladder, disagree with the agile manifesto. But what I’ve seen are a lot of roads paved with right intentions, but then things go awry because of the culture in place.

So my tip here is simple: empower your people, make them aware, accountable and responsible for their decisions. Getting down to the most basic thing: as human beings, we always want to get better. And I’m sure you’ll.

Closing remarks – updated

After writing the original article, I had some feedback from a friend of mine, Marcos Garrido. He told me, and I quote: “You know you’ve reached somewhere in your agile implementation when your team stops discussing The Process and starts discussing The Product“. I’ve had teams going up thru this phase and forward, and I know it: we’ve just ousted our bad, old habbits. So it might serve you as well as a good landmark that you’re heading to the right direction.